The following essay was another part of my recent course on American Music. and was written in response to the following question:

The following essay was another part of my recent course on American Music. and was written in response to the following question:

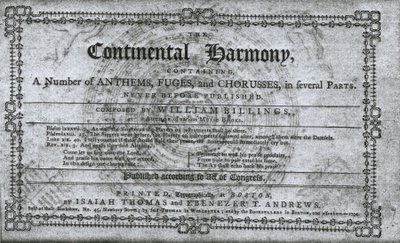

Q. Read William Billings’ prefaces to his Continental Harmony – both “To the several Teachers of MUSIC…” and “A commentary on the preceding rules…”. Comment on what these treatises seem to say about Billings himself: his sense of humor, his ability as a teacher, and his views on music, especially vocal music.

Billings may be better known today than he was even just a few years ago, but he still needs advocating. His music is simply wonderful

The Boston composer William Billings (1756-1800) represented one pinnacle of the uniquely American musical flowering in the latter 18th century. Unique, because although the music was European in background, it was very different from the music of Europe of that time. By the time of Billings’ birth, J.S. Bach was dead and Handel had but three years to live and the Baroque style that had been perfected by those two masters was evolving, not least through the medium of Bach’s son, Carl Philip Emmanuel, into the Classical style that would peak during Billings’ lifetime in the works of Haydn, Mozart and early Beethoven.

None of this music played any significant part in Billings’ development. Instead, Billings reached back, through the writings of earlier composers and psalter compilers such Willaim Tans’ur and John Playford, to older styles dating back to the Renaissance. But the music of Tans’ur and his followers never aspired to the level, of, for example, a Thomas Tallis or John Shepherd. It was strictly practical writing for small groups of people with limited resources, lacking in many cases any accompanying instrument such as an organ. This was music for the parish church and concentrated on settings of the Psalms. A ‘do-it-yourself ‘element was a necessity – practitioners were frequently self-taught, given the difficulties of gaining a musical education in an isolated rural region of England. The American colonies could be considered in some respects as further flung regions of England; it is thus unsurprising that music making of this type, particularly with the strong religious sentiment of its practitioners, would flourish in the New World.

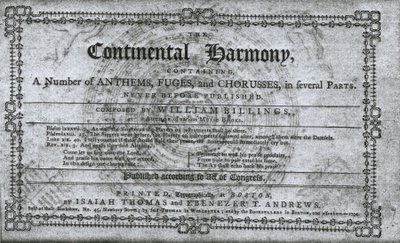

Billings published four volumes of psalm settings, fuging tunes and anthems during his life, beginning with The New England Psalm Singer, published in 1770. This was followed by The Singing Master’s Assistant, (1778), the Psalm Singers Amusement (1781) and the Suffolk Harmony (1786). The early volumes sold well, the latter less so. By the time The Continental Harmony was published in 1792, Billings was in financial difficulties and his last work failed to restore his fortunes. He may well have been aware that The Continental Harmony was likely to be his swansong given his age, changing public tastes and his financial problems, and writes within from the point of view of someone summing up his discoveries and attitudes to music and music performance. Now let’s consider the work itself.

Approaching the writings of William Billings from the point of view of a sophisticated listener but a rudimentary at best scholar of the language of music, I find myself drawn immediately into the role of student to Billing’s master. This is helpful in gaining an understanding of Billing’s persona as I am already casting myself in my mind back into a New England home, sitting alertly in a wooden chair, listening to the words of the Master as he imparts his knowledge.

And alert I would have to be, for Billings packs a lot of information into his long sentences. Nonetheless, his approach is methodical and well ordered. He begins with The Continental Harmony with a series of lessons directed to ‘the several TEACHERS OF MUSIC, in this and adjacent states”. Note the reference to teachers. Billings is laying out the syllabus and principles here that he believes should be taught, and is giving the local choirmaster a comprehensive set of guidelines by which to do so.

The first lesson, “The Gamut”, consists of tabulated listing of the notes of a scales for Tenor or Treble, Counter and Bass complete with their soundings as fa-mi-sol-la. Immediately, it is apparent that Billings is approaching the pupil as singer, which is as it should be for a book of song, but indicates that Billings is tailoring his musical teaching with practice in mind, as opposed to more abstract theorizing. Billings points out the whole and half note relationships, taking time out even at this early juncture to point out a common mistake of singers singing a B mi note as C fa. In doing so, he shows an empathy with the trials of many a choirmaster as well as the fruits of his own experience.

Swiftly he moves onto “Lesson II On Transposition”, where in two long sentences that need several readings to grasp, he lays out the travels of mi away from B as the key changes and the relationship of fa, sol, la etc. to mi after such changes. Again, practical advice for singers.

Lesson III on “Cliffs” (the 18th century spelling of clefs), introduces us to the written stave and the familiar bass clef, the identical treble and tenor clefs – the G clef – and the unusual counter clef that gives the middle line of the stave the identity of C. In a note Billings tells us how far, in intervals, a note set by one particular clef differs from that same note defined by a different clef and ends by defining the octave as any sound plus a seventh.

Lesson IV, “On Characters” defines all the notes by duration, from semibreve down, through minum, crotchet, quaver, semiquaver and demisemiquaver. He points out the changes in note duration from systems in the past where the semibreve was the shortest note rather the longest. He introduces the equivalent rests, and the additive terminology that adds one third to length of any note– the dot – known at the time as the Prick of Perfection but which Billings prefers to name the Point of Addition.

Billings then introduces us to the modifying elements that affect the notes he has just defined – the Flat, the Sharp, a Repeat character, the Slur – ‘a form like a bow, drawn over or under the heads of two, three or more notes, when they are to be sung to but one syllable” (an explanation that personally explains slurs more effectively than any I have come across). He gives us the bar divide, the Direct to show the placement of the first note of the next staff, the Natural, and the Mark of Distinction, a quotation-mark like character set over a note to indicate it should be ‘distinct and emphatic’ - a character that ‘when properly applied and rightly performed, is very majestic”. It’s worth noting here the value of the long abandoned habit of capitalizing the opening letter of a significant word that Billings, along with all contemporary writers of his age, uses in large measure. It is a wonderful aid to understanding.

Lesson VI covers the pacing of music from slow to fast. Billings begins with the adagio, and details a very precise way for the conductor – the choirmaster – to beat out this pace – or mood as Billings calls it. Each crotchet should be beat using the method “first strike the ends of the fingers, secondly the heel of the hand, and thirdly, raise your hand a little and shut, and fourthly, raise your hand still higher and throw it open at the same time”. What a wonderfully expressive motion this is, surely the method that Billings himself used. Billings very precisely sets the true time of each crotchet as one second, defined by the periodicity of a pendulum thirty nine and two tenths inches long. Should you not have such a pendulum, Billings even tells you how to make one “of common thread well-waxed, and instead of a bullet (as weight) take a piece of heavy wood turned perfectly round, about the bigness of pullet’s egg, and rub them over, either with chalk, paint or white wash, so that they may be seen clearly by candlelight.” Billings was clearly a practical man capable of some invention, as would befit a man who made his living primarily as tanner. Also the one of first, if not the first, in a long line of American inventor-composers! He also has strong grasp of the physics of pendulum periodicity, being able to calculate precisely the length needed for a desired timing.

Largo mood, “in proportion to the adagio as 5 is to 4”, follows with Billings providing pendulum lengths for beating in crotchets or minums. Next is allegro, beat as adagio except with minums replacing crotchets. Two from Four or 2/4 time follows, with each crotchet as half a second – a more manageable pendulum of nine inches and eight tenths!

Billings then switches from these common time moods to consider two moods, 6/4 and 6/8, with 6 crotchets and 6 quavers to the bar respectively, judging these “neither common nor triple time, but compounded of both, and, in my opinion, they are very beautiful movements.”

Following come three triple time moods. These are 3/2 time – each bar containing three minums, two beat down and one up. Again we are given precise hand movements “let your hand fall, and observe first to strike the ends of your fingers, then secondly the heel of your hand, and thirdly raise your hand up, which finishes the bar”. Then Three to Four (3/4), similar to 3/2 except crotchets are now used instead of mimums. Logically, Billings finishes with 3/8 – ‘an indifferent mood, and almost out of use in vocal music” where the beat is defined by the quaver.

Billings takes time in lengthy footnote to explain exactly the relationship of the numbers used in these time signatures, the named notes, and their place in the bar. In the same footnote, he gives performance instructions for the singer to negotiate figures placed over the bar, such as a 3 above three tied notes, a situation where you must sound the three notes in same the time it would normally take to sound two of the same kind - directions easier to grasp “by practice than precept, provided you have an able teacher”.

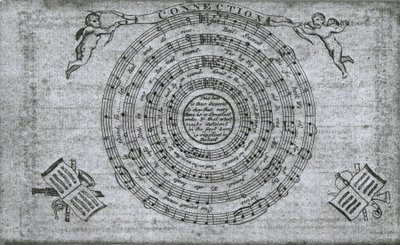

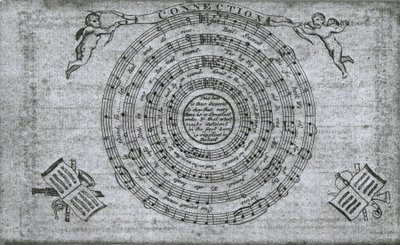

Now we move onto more complex concepts. Lesson VII covers “syncope, syncopation or driving notes”, that “have not been sufficiently explained by any writers I have met with”. Using no more than the musical materials that he has already given us, Billings demonstrates, in his first example, in the Allegro mood (i.e. two minums to the bar or 2/2 time), the equivalence of a minum between two crotchets in a bar to two tied crotchets between two untied. This is syncope.

His second example, again Allegro, with a bar containing a crotchet followed by a dotted minum. Here one beat consists of the crotchet, plus half the minum that is carried back, and the second beat is the last half of the minum plus the point of addition.

His third example, illustrating syncopation, shows the effect of ties that cross bar lines. Here Billings is not clear, and the first two examples that he shows as being the same do not seem to be so, although a third example he gives us is equivalent to the second. Sowing confusion in a subject ‘that has not been fairly explained by any of our modern authors’ does little to separate Billings from his contemporaries, but is perhaps explained by typographical errors – again his “Example 5th” shows inconsistency as Billing reiterates his ideas of syncope and syncopation using different time signatures.

Finally, Billings concludes his series of lessons with the statement that there “are but two primitive keys in music, viz. A, the flat key, and C, the sharp key” and “these two keys should be well understood; they must be strictly enquired into by all musical practitioners; for without a good understanding of their different natures, no person can be a judge of music.” Furthermore, Billings insists that words be set to flat keyed tunes to portray the sad, and to sharp keys for the happy. Clearly Billings has a strong attachment to a relatively simple set of compositional rules, all of which were being greatly expanded by European developments during latter half of the 18th century.

Having relatively tersely laid out the basic rules of music, Billings then chooses to develop his themes at much greater length by the strategy of a question and answer dialogue between a doubtless idealized student and Mr. Billings, the music master. This dialogue is carefully constructed to follow the plan of his lessons. Initially, we learn that “The Gamut” is Greek in origin but owes its current form to a monk, Guido Aretinus, “whose name deserves to be recorded in the annals of fame” and who was probably ‘inspired with this invention, by Him, who is the Author of harmony itself”. Billings here underscores his belief in the great religious value of music, a sentiment out of sympathy with the strict beliefs of the Puritans. To make his music acceptable to as large a part of the New World, Billings would need to underscore its divine origins as much as he could.

In such vein, Billings continues with speculation about the music of the original Royal Psalmist, King David himself, ultimately suggesting that The Gamut is none other than “King David’s Scale”. Shrewd speculation, that regardless of its accuracy, stamps Billing’s method with Biblical approval.

In great and turgid detail, Billings then attempts to explain all the transpositions of B first mentioned in Lesson II, a passage to which the ‘student’ responds, “I doubt not but I shall reap the benefit of it”, and after parsing it repeatedly he may well do so.

Billings informs us that he know of only three clefs, the F, G and C, the former two being shackled to the stave, the latter moveable as stated in Aaron Williams in The Universal Psalmodist, 1764, one of Billing’s own reference sources.

Now we diverge from the lesson plan, no doubt to accommodate a practical concern of Billings, to consider choral performance practice. After defining the difference between a medius – a man singing the upper part of a four part musical piece two octaves above the bass – and a treble, a woman singing the same part three octaves above the bass, we then enter a consideration of the worth of each. For Billings, they are best set together for “such a conjunction of masculine and feminine voices is beyond expression, sweet and ravishing, and is esteemed by all good judges to be vastly preferable to any instrument whatever, framed by human invention.”

This is most significant statement. It tells us exactly why Billings chose to be a composer of choral music and not instrumental, and it is clear, as Billings expounds further on the design of choral music, that the interplay of the sung voice is the one element of music that truly inspires the composer.

After this illuminating diversion, we return to plan as Billings informs of the bar filling properties of the semibreve rest, before once again considering the performance practice of the hold, not mentioned in the lessons. Billings has scant regard for this device, where a note is sung for longer than the time value of the note, as it disrupts the time structure of the piece and should not even be present in a properly constructed bar. In doing so, he declares his independence from the written principles of two earlier psalmodists, John Arnold and William Tans’ur.

Billings continues in this vein, considering the role of the double bar in psalms – a point to take a breath according to some – but for Billing a point to merely catch breath while keeping a good sense of time. Billings then reminds us that in psalms double bars are placed at the ends of lines, indicating to the congregation where to stop so they can keep some sense of place using the old practice of lining out, or retailing, as Billings calls it. This gives Billings a chance to rail at the practice of lining out, “which is so destructive to harmony”, and aligns himself with the advocate of musical literacy, Dr. Watts.

We then learn of the old long notes values, the Large, the Long and the Breve, that have supplanted by the shorter values beneath the semibreve, and Billings again, in the manner of his earlier explanation of the transitions of B- mi, expounds on the difference between Common and triple time, doing his best to set to rest the misperception that common time is slow music, and triple time fast, ending with the characteristic assertion “You may depend on the infallibility of this rule in any mood whatsoever”.

He again asserts that 6/4 and 6/8 time are composed of elements of Common and triple time, emphasizing that 6/8 “largely partakes of the beauties of both”, before turning has attention again to performing practice, precisely defining the speeding up or slowing down of a musical line that is marked for such as one quarter of the current speed. Billings approves of grace notes but not for note values under half a beat, as “it makes the sound like notes tied together, in threes, which is very false and entirely spoils the air (Billing’s italics)”. Again, Billings demonstrates he has a very clear concept of just how he wants his music to sound.

Back again to the consideration of key, which is best, flat or sharp? Here, Billings expounds on his “flat = sad, sharp = glad” concepts, with a lengthy consideration of the setting of psalms. He quotes the uplifting Psalm 95, “let us make a joyful noise” contrasting it with lamentations such as Psalm 42, “O my God, my soul is cast down with me”, assigning the sharp key to the former and the flat key to the latter. With great enthusiasm he relates how those latter flat key settings “affect us both with pleasure and pain, but the pleasure is so great it makes even the pain to be pleasant…(Billing’s italic)”, but then counters with the exaltation and “ecstasy of joy” that tunes in the sharp key produce. He resolves that neither claim any superiority, and relates a charming story of the susceptibility of Alexander the Great to music, leaping up to slay his enemies upon hearing the sharp key, yet being soothed to weeping by the flat – all in the course of a brief performance. Nonetheless, he ends by declaring that should a vote be taken of all music lovers, the flat key would easily win. On further query by his pupil, he reveals that although men may regard each key equally well, women, nine-tenths no less, would prefer the flat.

Which leads again to another lengthy and dense paragraph on the mechanics of music, seeking to explain the transpositions of keys, a concept more effectively diagrammed than described, but he slips in a disarming poetic verse (previously published in The New England Psalm Singer) to explain the migrations:

By flats the mi is driven round

Till forc’d on B to stand its ground

By sharps the mi’s led through the keys

Till brought home to its native place

His ‘student’ interjects with the not-unreasonable statement as to “the necessity of transposing B-mi from one place to another, for if the tune must always end on A or C, I do not see any great difference between a tune that is set in its native place and one that is transposed”. Billings responds by stating that such transpositions serve to keep the music on the stave, but, more importantly, let the music give “a variety of airs” – a way of saying that every melody has a key that suits its temperament better than any other, and also implying that ending every tune on a C or an A is an easily broken rule.

By now it is clear that Billings is doing no less than codifying all the principles upon which he based his own compositional method. Clearly he feels it important to share this knowledge, suggesting a strong belief in both the originality and substance of his thought.

He continues to parry practices stated by other composers. A well-pitched tune is one where the performers can clearly produce the highest and lowest note, but Billings allows for exceptional singers who can carry a tune “perhaps five or six notes too high, or too low” yet “oftentimes the greatest masters of composition set some of their pieces too or too low” (and there is a strong sense here that Billings is including himself in this class) as the ‘student’ will soon comprehend once he begins composing.

Billings then goes on to state the importance of the third note above the key note, plus the sixth and seventh as important guide notes for composition, rejecting fourths, fifths and the octave. He offers some conjecture as to the singers practice of hitting sharpening the B-mi, being drawn so by the key note. Clearly based on his own observations, he comments on the difficulty that even well-trained singers have harmonizing upon first meeting and performance, assigning the clash to differences in the singers transitions from one note to another. A good choirmaster, by laying emphasis on the first and third beats of a bar in common time, or the first beat in triple time, can effectively knit his singers together.

This advice, with its emphasis on accenting, elicits an extraordinary footnote from Billings who, answering a ‘critic’ who notes the lack of such attention on accenting in the earlier The New England Psalm Singer , proceeds to confess that he began composing without understanding “either tune, time or concord (Billings’ italics)”. After this confession, he vacillates between humility and hubris with the latter triumphing. Billings must have been sensitive to his own lack of formal musical training and, inevitably, his growth as a composer would encompass works that he now regards less well. Nonetheless this pugnacious apology is overdone and unnecessary – a strong pointer to an undercurrent of insecurity in the man.

Moving on, we read Billings’ opinion of the interval of a fourth, decidedly casting it as a dischord (contrasting with the opinion of Thomas Walter as stated in The Grounds and Rules of Musick Explained). He then considers the use of dischords in general, confessing that he has formulated no rules to handle them, going so far to acknowledge that “when fancy gets upon the wing, she seems to despise all form, and scorns to be confined or limited by any formal prescriptions whatsoever”. It becomes clear that Billings compositional method begins with such freedom, and involves the attempt to organize and harmonize the latter parts of the work to this, this being “the grand difficulty in composition”.

A similar consideration of concords reveals Billings fondness for thirds, sixths and tenths – “the octave to a greater third” – which he considers to be the greatest concord found in nature.

Returning to performance, Billings states his preference for singers with a musical ear rather than voice, “for any one that has not a musical ear is no better judge of musical sounds than a blind man is of colours”. He conjectures on the global origin of the best singers, allowing that singers from the tropics, “the blacks brought here from Africa”, are better singers than native Americans. No mention is made that those same blacks would be slaves.

Billings defines an Anthem for us, making clear that he considers that the form of this “divine song” to be of his own creation.

Finally, Billings returns to his theme of the innate Godliness of music by quoting (through the “scholar”) the Italian proverb, “God loves not him who loves not music”. Claiming that there is no such thing as one who does not love music, Billing’s qualifies his opinion by extending his definition of music well beyond the sound of the choir into abstractness – “the usurer in the sound of interest upon interest (Billings’ italics)”. For Billings, music is “nothing more than agreeable sounds” and “that sound which is most pleasing is most musical.” Only the deaf are excluded (although surely a deaf usurer would rejoice as well as any other in the music of his accumulating interest). Billings’ statements here, although they do not hold up to logical analysis, tell us much about the regard in which he holds music; a regard that is on the highest level and is effectively equivalent to any meaningful and spiritual human endeavor.

He concludes with words of advice to his ‘student’, neither be overconfident or unduly insecure, seek the truth, always be open to new knowledge, but ultimately to be most concerned with the essence of music, an essence irrevocably bound up in faith and allowing entry into “that land of Harmony, where we may in tuneful Hosannahs and eternal Hallelujahs, Shout the REDEEMER (Billings’ italics and capitals)”.

Never one to let an interesting point go said without extra comment, Billings adds in a footnote that “ignorance and conceit are inseparable companions” and expounds with another tale lambasting churchmen who fail to understand the use of appropriate meter for whichever psalm their service requires. A final footnote ends on a more spiritual plane by quoting Milton from Paradise Lost – a short section describing a unison performance of a sacred text “such concord is in heaven”.

The Continental Harmony reveals Billings to be, if not an intellect of the first ranking, a thoughtful, inquisitive and confident individual, not to overbearing extent of excising self-doubt, but clearly an attractive advocate of his music. Indeed, a man of strong opinion as to the worth of music in general, and the competent understanding and practice of such. A strong streak of individualism runs through his works, casting him clearly in the forefront of a long line of ruggedly independent American composers who choose to work with the materials available to them, or invent new ones, rather than simply accept prevailing European cultural concepts. Like all in such a position, he is forced to become teacher to ensure the promulgation of his ideas, but this is a role he clearly relishes and his enthusiasm is very appealing.

All I am going to write is based solely on what I have from the Heroes To Zeroes album, and I don't know any of their other music (other than the snippet played in the Hi Fidelity movie).

All I am going to write is based solely on what I have from the Heroes To Zeroes album, and I don't know any of their other music (other than the snippet played in the Hi Fidelity movie).